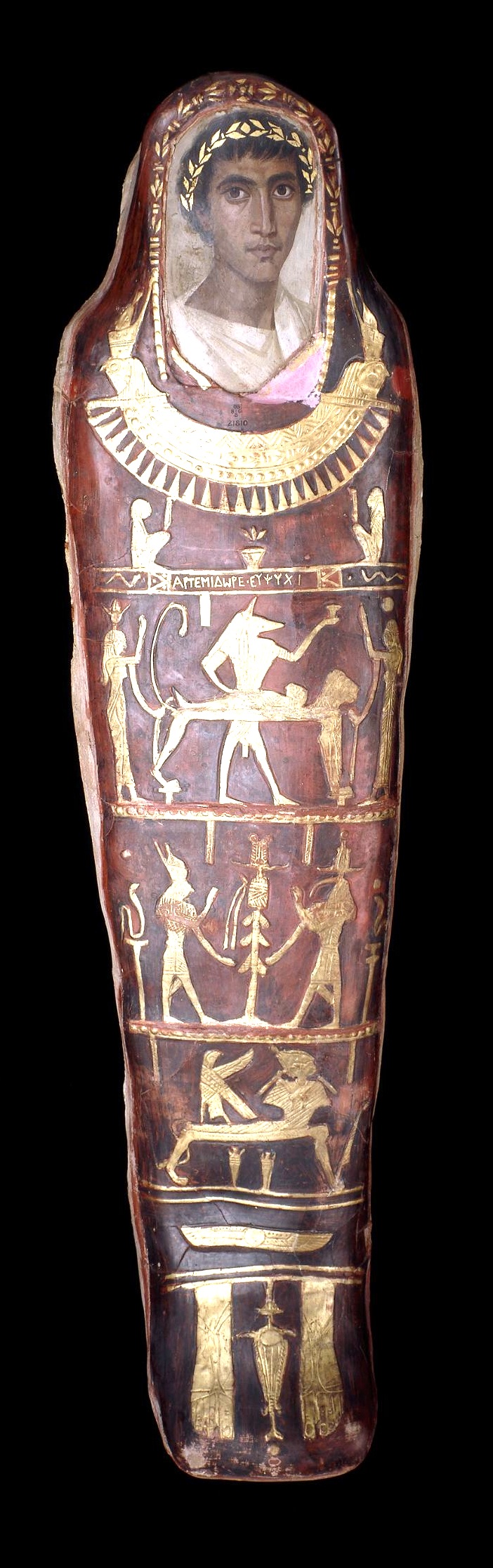

Figure 1: The Mummy of Artemidorus, AD 100-120 (In the British Museum).

The Life of Bishop Pisentius is very important in many ways not least because it sheds some light on what Copts of the Classic Period,[1] at least, thought of death and afterlife. Saint Pisentius[2] (548 – 632 AD) was selected bishop of Coptos,[3] in deep Upper Egypt, in AD 599, and remained bishop there until his death.[4] The Life of Bishop Pisentius is written in the 7th Century by his disciple, John the Elder, but there are other recensions where one finds the names of Moses and Tawudoros (Theodore) as authors too.[5] We have it in Coptic Sahidic, Coptic Bohairic (Memphitic), Arabic and Ethiopic versions;[6] and some of these were published in English:

- The Sahidic version: This was translated in 1913 by E. A. Wallis Budge in his Coptic Apocrypha in the Dialect of Upper Egypt under the title The Life of Bishop Pisentius, by John the Elder.[7] This manuscript (Brit. Mus. MS. Oriental No. 7026) dates to AD 985. In his book, Budge included an excellent Introduction on Bishop Pisentius.[8]

- The Bohairic (Memphitic) version: This was edited by E. Amélineau in 1889,[9] and is attributed to John the Presbyter and Moses, Bishop of Coptos (he succeeded Pisentius). This version, unlike the Sahidic version, contains the story of Pisentius’ conversation with the mummy, the story that interests us here. Budge translated the story, and added it as an appendix to his translation of the Sahidic version.[10] It is the story in this Bohairic version which we use here under the title The Life of Bishop Pisentius.

- The Arabic version: There are many Arabic versions. In 1930, DeLacy E. O’Leary used two Arabic manuscripts in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Arabe 4785 and Arabe 4794), which he didn’t date, to publish his The Arabic life of S. Pisentius,[11] and he says both manuscripts contain the miracle of the saint’s “converse with the dead”.[12] The book includes fifty six wonders of the saint, and it is The Thirty Two Wonder which deals with Pisentius’ conversation with the mummy.[13]

Saint Pisentius was bishop of Coptos at the time of the Persian invasion of Egypt, in AD 619, when Khosraw II Pevez took Egypt from the Byzantines. This third Persian occupation of Egypt (619-629 AD)[14] lasted for only ten years, and ended when Heraclius I wrestled Egypt back from the Persians. Once Bishop Pisentius got the news of the approaching Persians, he wrote a pastoral letter to all his diocese in which he said, “Because of our sins God has abandoned us; he has delivered us to the nations without mercy;”[15] and he, together with his disciple and biographer John, fled some 23 miles south to the mountain of Tjîmi[16] (called Shama شامة in Arabic manuscripts)[17] in Western Thebes (Luxor), where he stayed in retreat for ten years,[18] “praying night and day that God would save the people from bondage to those cruel nations.”[19] Only John knew his hiding place, and he used to take him a supply of food and drink each Sabbath day.[20]

In the recesses of that mountain, Pisentius found a tomb in which he took refuge. It possessed “a large hall about 80 feet square, and its roof was supported by six pillars. This hall was made probably under one of the kings of the New Empire, and had been turned at a much later period, perhaps in one of the early centuries of the Christian era, into a common burial-place for the mummies of people of all classes. At all events, when John was taken there by his master the hall contained many mummified bodies, and the air was heavy with the odour of funerary spices. Pisentius and his disciple opened some of the coffins, which were very large, with much decorated inner coffins. One mummy was swathed in silk, and must therefore have belonged to the third or fourth century of our era. As John was about to leave Pisentius he noticed on one of the pillars a small roll of parchment, and when Pisentius had opened it he read therein the names of all the people who had been buried in that tomb. The roll was probably written in demotic, and it is quite possible that the bishop could read this easily.”[21]

In that Pharaonic hall, used as little necropolis for some mummified dead from the Roman period, Pisentius had a curious encounter and intriguing conversation with a mummy, which was heard by John when he returned the following Saturday with water and food supply for the week, and later documented it in his book. We know that the mummy belonged to a man from Erment;[22] and although we are not given his name, his parents’ names we are given as Agricolaos and Eustathia, and that they were Hellenes. Furthermore, we are told that the family worshipped Poseidon, the Greek God of the Sea. That encounter with that mummy reveals a great deal of what Copts of that age thought of death and afterlife.

Let us read together that fascinating story in The Life of Bishop Pisentius as it was told in the Bohairic (Memphitic) version, and which was published by E. A. Wallis Budge:[23]

And it came to pass on a day whilst my father was still with me in the mountain of Tjîmi that my father said unto me, ‘John, my son, rise up, follow me, and I will shew thee the place wherein I repose and pray, so that thou mayest visit me every Sabbath and bring me a little food, and a little water to drink wherewith to support my body.’ And my father rose up, and walked before me, and he was meditating on the Holy Scriptures of the Spirit of God. And when we had walked about three miles, at least so the distance appeared to me, we came to a path which was in the form of a door which was wide open. And when we had gone inside that place, we found that it had the appearance of being hewn out of the rock, and there were six pilasters rising up against the rock. It was fifty-two cubits in length, it was four-cornered, and its height was in proportion [to its length and breadth]. There was a large number of bodies which had been mummified in it, and if thou wast merely to walk outside that place thou wouldst be able to smell the ‘sweet smell’ (i.e. spices), which emanated from these bodies. And we took the coffins, we piled them up one on top of the other — now the place was very spacious — ……..[24] The swathings wherein the first mummy, which was near the door, was wrapped, were of the silk of kings. And his stature was large, and the fingers of his hands and his toes were bandaged separately.[25] And my father said, ‘How many years ago is it since these [people] died? And from what nomes do they come?’ And I said unto him, ‘It is God [only] Who knoweth.’ And my father said unto me, ‘Get thee gone, my son. Sit in thy monastery, take heed to thyself, this world is a thing of vanity, and we may be removed from it at any moment. Take care for thy wretched state. Continue thy fastings scrupulously. Pray thy prayers regularly hour by hour, even as I have taught thee, and do not come here except on the Sabbath.’ And when he had said these things unto me, I was about to come forth from his presence, when looking carefully on one of the pilasters, I found a small parchment roll. And when my father had unrolled it, he read it, and he found written therein the names of all the people who were buried in that place; he gave it to me and I put it down in its place.[26]

And I saluted my father, and I came away from him, and I walked on, and as he shewed me the way he said unto me, ‘Be thou diligent in the work of God so that He may shew mercy unto thy wretched soul. Thou seest these mummies; needs must that every one shall become like unto them. Some are now in Amenti,[27] — those whose sins are many, others are in the Outer Darkness, and others are in pits and basins which are filled with fire, and others are in the Amenti which is below, and others are in the river of fire, where up to this present they have found no rest. Similarly others are in a place of rest, according to their good works. When a man goeth forth from this world, what is past is past.’ And when he had said these things unto me, he said, ‘Pray for me also, my son, until I see thee [again].’ So I came to my abode, and I stayed there, and I did according to the command of my holy father, Abba Pisentius.

And on the first Sabbath I filled my water-pot with water, and [I took] a little soft wheat, according to the amount which he was likely to eat, according to his command (he gave [me] the order [to bring] two ephahs[28] which he distributed over the forty days),[29] and he took the measure and measured it, saying, ‘When thou comest on the Saturday bring me this measure [full] with the water.’ So I took the pitcher of water and the little soft wheat, and I went to the place wherein he reposed and prayed. And when I had come in to the abode I heard some one weeping and beseeching my father in great tribulation, saying, ‘I beseech thee, O my lord and father, to pray unto the Lord for me so that I may be delivered from these punishments, and that they may never take hold of me again, for I have suffered exceedingly.’[30] And I thought that it was a man who was speaking with my father, for the place was in darkness. And I sat down, and I perceived the voice of my father, with whom a mummy was speaking. And my father said unto the mummy, ‘What nome dost thou belong to?’ And the mummy said, ‘I am from the city of Ermant.’ My father said unto him, ‘Who is thy father?’ He said, ‘My father was Agrikolaos and my mother was Eustathia.’ My father said unto him, ‘Whom did they worship?’ And he said, ‘They worshipped him who is in the waters, that is to say Poseidôn.’ My father said unto him, ‘Didst thou not hear before thou didst die that Christ had come into the world?’ He said, ‘No, my father. My parents were Hellenes,[31] and I followed their life. Woe, woe is me that I was born into the world! Why did not the womb of my mother become my grave?[32] And it came to pass that when I came into the straits of death, the first who came round about me were the beings “Kosmokrator”,[33] and they declared all the evil things which I had done, and they said unto me, “Let them come now and deliver thee from the punishments wherein they will cast thee.” There were iron knives in their hands, and iron daggers with pointed ends as sharp as spear points, and they drove these into my sides, and they gnashed their teeth furiously against me. After a little time my eyes were opened, and I saw death suspended in the air in many forms. And straightway the Angels of cruelty snatched my wretched soul from my body, and they bound it under the form of a black horse, and dragged me to Ement (Amenti). O woe be unto every sinner like myself who is born into the world! O my lord and father, they delivered me over into the hands of a large number of tormentors who were merciless, each one of whom had a different form. O how many were the wild beasts which I saw on the road! O how many were the Powers which tortured me! When they had cast me into the outer darkness I saw a great gulf, which was more than a hundred cubits deep,[34] and it was filled with reptiles, and each one of these had seven heads, and all their bodies were covered as it were with scorpions. And there was another mighty serpent in that place, and it was exceedingly large, and it was a terrible sight to behold; and it had in its mouth teeth which were like unto pegs of iron. And one laid hold of me and cast me into the mouth of that Worm, which never stopped devouring; all the wild beasts were gathered together about him at all times, and when he filled his mouth all the wild beasts which were round about him filled their mouths with him.’

My father said unto him, ‘From the time when thou didst die until this day, hath no rest been given unto thee, or hast thou not been permitted to enjoy any respite from thy suffering?’ And the mummy said, ‘Yes, my father, mercy is shewn unto those who are suffering torments each Sabbath and each Lord’s Day. When the Lord’s Day cometh to an end, they cast us again into our tortures in order to make us to forget the years which we lived in the world. Afterwards, when we have forgotten the misery of this kind of torture, they cast us into another which is far more severe. When thou didst pray for me, straightway the Lord commanded those who were flogging me, and they removed from my mouth the iron gag which they had placed there, and they released me, and I came to thee. Behold, I have told you the conditions under which I subsist. O my lord and father, pray for me, so that they may give me a little rest, and that they may not take me back into that place again.’ And my father said unto him, ‘The Lord is compassionate, and He will shew mercy unto thee. Go back and lie down until the Day of the General Resurrection, wherein every man shall rise up, and thou thyself shalt rise with them.’ God is my witness, O my brethren, I saw the mummy with my own eyes lie down again in its place, as it was before. And having seen these things I marvelled greatly, and I gave glory unto God. And I cried out in front of me, according to rule, ‘Bless me,’ and then I went in and kissed his hands and his feet. He said unto me, ‘John, hadst thou been here a long time? Didst thou not see somebody or hear somebody talking to me?’ And I said, ‘No, my father.’ He said unto me, ‘Thou speakest falsehood, just as did Gehazi when he uttered falsehood to the prophet, saying, “Thy servant went no whither.”[35] But since thou hast seen or heard, if thou tellest any man during my lifetime thou shalt be cast forth (i.e. excommunicated).’ And I have observed the order, and I have never dared to repeat it to this very day.

Here we have an extraordinary encounter of the seventh century saint, Bishop Pisentius of Coptos, with a Hellene mummy that was lodged, with other mummies, in a Pharaonic hall in the mountain of Tjîmi, in Western Thebes, sometime in the third or fourth century. The encounter was witnessed by John, Pisentius’ disciple, and he recorded it after the death of the bishop in AD 632. It sheds, as the reader has seen, important light on the Coptic perceptions and beliefs of the destiny of man at death and then after it. We can summarise these in the following:

1. At man’s death, his soul departs from his body; it does not sleep or go into coma until the Last Day. Furthermore, all souls are immortal and accountable to God.

2. Following death, all souls go to the underworld, to spend an intermediate phase of their existence until the Judgement Day. This underworld, the Copts called Amenti, which is an ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic word and means “the hidden place, or land, the West, the abode of departed spirits, the name of the first division of the Other World”.[36] The equivalent word in Greek is Hades; in Hebrew Sheol; in English Hell; and in Arabic الجحيم.[37]

3. Amenti is composed of different places to accommodate souls with different degrees of sin. These places, or stations, are not immediately clear in The Life of Bishop Pisentius, most probably as a result of some careless copyist. In it Pisentius says to his disciple John:

Thou seest these mummies; needs must that every one shall become like unto them. Some are now in Amenti, — those whose sins are many, others are in the Outer Darkness, and others are in pits and basins which are filled with fire, and others are in the Amenti which is below, and others are in the river of fire, where up to this present they have found no rest. Similarly others are in a place of rest, according to their good works.[38]

The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, on the other hand, gives it a bit different:

Thou hast seen, O my son, all these dead cast aside to warn us that we shall be like them. Some of them are those who are gnashing their teeth, others are in the outer darkness, others are in torment and in the pit full of fire and brimstone, their abode in the lowest hell, and some of them are in the river of fire and have never been able to get out to this present time, and some of them are in places of repose because of their works.[39]

By comparing the two versions, and by resort to relevant Biblical texts, one can come to a clearer understanding: It seems that the Copts had in mind four stations in Amente:

a. The “Place of Rest”, “Places of Repose”, which some souls occupy because of their [good] works while in the body on the earth.

b. The “River of Fire” which some sinful souls must cross in order to be purified, and be able to be admitted to the “Place of Rest” at some stage. We have seen this “River of Fire” in The Life of Apa Cyrus.[40] The “River of Fire”[41] (or the “Fiery Stream”[42]) is mentioned in Daniel 7:10, but not in the way intended in The Life of Bishop Pisentius, The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, or The Life of Apa Cyrus.

c. The “Outer Darkness”, into which the soul of our mummy was cast, is where those gnashing their teeth, a sign of pain, sorrow and grief for realising one’s own sins in full, are thrown. This “Outer Darkness” is mentioned, associated with weeping and gnashing of teeth, in so many verses in the Gospel according to St. Matthew, such as: “Then said the king to the servants, Bind him hand and foot, and take him away, and cast him into outer darkness; there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”[43]

d. The “Pit full of Fire and Brimstone (Sulphur)”,[44] or “”Pits and Basins which are filled with Fire”,[45] exist at the bottom of Amenti, in the lowest hell. This seems to be retained for the devil and the ungodly who deserve eternal punishment. Both Old[46] and New Testaments refer to it, particularly in the Book of Revelation, such as: “And the devil that deceived them was cast into the lake of fire and brimstone, where the beast and the false prophet are, and shall be tormented day and night for ever and ever;”[47] [48]and: “But the fearful, and unbelieving, and the abominable, and murderers, and whoremongers, and sorcerers, and idolaters, and all liars, shall have their part in the lake which burneth with fire and brimstone: which is the second death.”[49]

4. The “River of Fire” is a fascinating station of Amente according to the Coptic concept. We quote here the relevant piece in The Life of Apa Cyrus:

I [Cyrus] have performed a few of the ascetic labours which God appointed for me, it is true, but how is it possible for us not to be afraid of the things which have been indicated to us by very many witnesses, that is to say, the river of fire, and the appearance before the Judge? And as for that river, everyone is bound to pass over it, whether he be a righteous man or whether he be a sinner, and it is right that thou shouldst pray on my behalf until I journey over that terrible road.

… If a man’s life upon this earth were to consist of one day only, he would not be free from sin. And, moreover, all flesh shall be purged by the fire.[50]

We find a similar passage in The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius under the Fifty Three Wonder:[51] as Pisentius approached his death,[52]John tells us:

[Apa Pisentius] prayed and offered supplication and said: ‘O martyr of Christ, Ignatius,[53] come to me and strengthen my faith: bring the crown which does not decay, with the rest of the athletes. Be with me until I reach the river of fire which flows before the just judge, where there is great and very dreadful fear.’ And I said to him: ‘O my father, after the penances thou hast endured in the world, and fastings, and prayers, and fatigues, and long vigils, dost thou fear the river of fire?’ And the blessed one answered and said: ‘Who is safe from crossing the fiery river? — I say to thee that if an angel came from heaven he would not escape its crossing before coming to the earth.’ And he informed me: ‘I shall cross it on the evening of the thirteenth day of the month Abib.’[54]

Now, I don’t think O’Leary’s translation of the Arabic text is entirely correct. His “Who is safe from crossing the fiery river? — I say to thee that if an angel came from heaven he would not escape its crossing before coming to the earth” must be ““Who is safe from crossing the fiery river? — I say to thee that if an angel came from heaven he must cross it in view of his coming to the earth.”[55] This gives the same meaning that Apa Cyrus wanted to convey: that everyone had to pass over the “River of Fire”, whether he is a righteous man or whether he is a sinner; that no man is free of sin even if his life on earth were to consist of only one day. Apa Pisentius reinforces that by saying even angels if they came to, and lived on, the earth will not be free from sin, and they too must pass through that fire for purification. This, in my opinion, does not mean that, in the Coptic mind, righteous men will definitely pass through this “River of Fire” – what it means is that no one, however saintly, deserves to go to the Place of Rest or Paradise by right: man can only do that through the grace of God. Both Apa Cyrus and Apa Pisentius, in their humility, showed this understanding, and Christ, we are told, showed his mercy to them: we do not know what happened to Apa Pisentius at his death, as his biography doesn’t tell us; however, we know from the Life of Apa Cyrus that Christ has taken the souls of Apa Cyrus and Apa Shenoute, who died a day earlier, to “the place of rest”.[56]

Apa Cyrus says, “All flesh shall be purged by fire”. This may give the impression that all souls will pass through the “River of Fire”, and get their sins washed away through suffering, and so will eventually be saved – i.e. a purgatory for all and a universal salvation. However, read in conjunction with The Life of Bishop Pisentius, one tends to think that only sinners in the “outer Darkness” may be able to do so – those in the “Pit full of Fire and Brimstone”, or the devil and the “ungodly” referred to in Revelation 19-21, will not.

5. The regular respite period which we have seen in The Ethiopian Synaxarium when it talks about Apa Cyrus is again emphasised here, however inadequately. In The Ethiopian Synaxarium we are told that those sinners who are being tormented in Amente get rest from their punishments “on the day of His holy Resurrection, from the ninth hour of the day preceding the Sabbath until the sun setteth on the First Day of the Week”; that is from 3 p.m. on Friday until sunset on Sunday.[57] In The Life of Bishop Pisentius, sufferers are shown mercy “each Sabbath and each Lord’s Day”[58], and in The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, the relief given is “on the night of Sunday, because it is the resurrection of Christ,” “from the ninth hour of the sabbath until the end of Sunday.”[59]

6. Copts have always prayed for their reposed in private and public prayer: they believe that prayer of the faithful on earth does help those departed souls in Amente – and this seems to be an old tradition. We have seen that once Pisentius prayed for the mummy, straightway “the Lord commanded those who were flogging me, and they removed from my mouth the iron gag which they had placed there, and they released me, and I came to thee.”[60] The soul knew of the power of prayer, and so it beseeched Pisentius: “O my lord and father, pray for me, so that they may give me a little rest, and that they may not take me back into that place again.”[61] And Pisentius, having faith in Christ’s mercy, says to the mummy, “The Lord is compassionate, and He will shew mercy unto thee. Go back and lie down until the Day of the General Resurrection, wherein every man shall rise up, and thou thyself shalt rise with them.”[62]

The description by the mummy of his illness that led to his death, the arrival of death, the dragging of his soul to Amente and its casting in the Outer Darkness, and the torments he has received in it, all make excellent figurative language. To take it literally in physical terms, rather than as a metaphor for the agonising pain that a sinful soul meets at and after death, is difficult. It is, however, very effective in bringing to listeners and readers the seriousness of the consequences of their living in sin. The Coptic Amente or underworld may be fearful and a place for suffering and pain; it, however, is also a place where many dead find their rest in peace, and many others experience temporary suffering as their souls are being purified, always being aware of their final salvation – in other words, side by side with sadness and despair exist joy and hope.

[1] An intelligent periodification of Coptic history has not been made yet, but I use “Coptic Classic Period” here to mean the history of the Copts from the introduction of Christianity to Egypt in the first century until the Arab occupation of Egypt in the seventh century. This period can be subdivided into several distinct periods.

[2] Also written Pisentios, Pisuntios and Pisentius; and in Arabic بيسنتاوس, بسنتاؤس, بسنتيوس, بسنتاووس, بسندة and بسنتى .

[3] Also Qift (قفط in Arabic). It is a city in the Governorate of Qena, some 300 miles south of Cairo, and 23 miles north of Luxor.

[4] For these dates, see: تاريخ المسيحية والرهبنة وآثارهما في أبروشيتي نقادة وقوص وإسنا والأقصر وأرمنت (Tārīkh al-Masīḥīyah wa-al-rahbanah wa-āthārihimā fī abrūshīyatay Naqādah wa-Qūṣ, wa-Isnā wa-al-Uqṣur wa-Armant) by Nabīh Kāmil Dāwud and ʻĀdil Fakhrī (Cairo, Institute of St. Mark for Studies in Coptic History, 2008); p.136.

[5] Ibid.; pp. 136-140.

[6] Ibid.

[7] E. A. Wallis Budge in his Coptic Apocrypha in the Dialect of Upper Egypt (London, 1013); pp. 258-334. The Coptic Sahidic text, Budge included in pp. 75-127.

[8] Ibid.; pp. xli-l.

[9] “Un évêque de Keft au VIIe siècle”, Mémoires présentes et lus à l’Institut égyptien II (Paris, 1889); introd., pp.261-332; text and trans., pp. 333-423.

[10] Coptic Apocrypha; pp. 322-330 include this story and two other stories which are not available in the Sahidic version.

[11] DeLacy E. O’Leary, The Arabic life of S[aint] Pisentius : according to the text of the 2 ms. Paris Bib. Nat. arabe 4785 and arabe 4794 in the Patrologia Orientalis; Tome 22, Fasc. 3, No. 109 (Paris, Firmin-Didot, 1930); introd., pp. 317-321; text and trans., pp. 322-488.

[12] In Arabe 4785, in 176.6; and in Arabe 4794, in 136.a-1 11.a. But it seems that, in his book, O’Leary uses Arab 4785 only in his translation of Miracle 32.

[13] Ibid., pp. 419-429.

[14] This invasion was undertaken by the Sassanid king, Khosraw II Parvez. Two previous Persian invasions occurred under the Archaemenids: the First Persian Period (525-402 BC) was inaugurated by Cambyses II who ended the 26th Dynasty, and established the 27th Dynasty (the 1st Persian Dynasty). The Second Persian Period (343-332 BC), which was established by Artaxerxes III, who conquered Egypt for a brief period, and founded the 31st Dynasty. This dynasty was ended by Alexander the Great.

[15] A. Butler: Arab Conquest of Egypt And The last Thirty Years of the Roman Dominion (Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 1902; ed. 1998); p. 85. This blaming of one’s sins for disasters was a common Christian explanation of historical events during the Byzantine times.

[16] Djîmé or Gemi.

[17] We know that Saint Pisentius started his monkish life in the same mountain. تاريخ المسيحية والرهبنة وآثارهما; p. 136.

[18] We know he stayed in hiding from the Persians for ten years (i.e., the whole ten years of the Persian rule) from The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 462.

[19] Arab Conquest of Egypt; p. 85.

[20] John stayed in a nearby monastery, most probably the Monastery of St. Phoebammon (Abe Fam) the Soldier (his martyrdom is celebrated in the Synaxarium on 27 Toba), which was close bye (west of Luxor and the Valley of the Queens by some 5 miles). تاريخ المسيحية والرهبنة وآثارهما; p. 314.

[21] Coptic Apocrypha; Introduction; p. xlviii.

[22] Erment (the modern town of Armant; Greek, Hermonthis), which is located about 8 miles south of Thebes. This is also the town from which Pisentius’ parents came (تاريخ المسيحية والرهبنة وآثارهما; 153).

[23] I have taken out words written in Coptic.

[24] Budge leaves several words without translation as he says their exact meaning is not clear to him (footnote no. 1 on p. 327). Looking at the Arabic text of the manuscript Arabe 4785, in Paris, which O’Leary published in his The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, one can see that the Arabic equivalent for the missing words is “ووجدنا الأرض التي كانت عليها الأموات وقد لانت كطين الفاخوري المعجون”. O’Leary translates these as “And we found the earth which was on the mummies to be soft like potter’s clay” (p. 421). I think the right translation should change the ‘on’ preposition used by O’Leary to ‘under’.

[25] Wrapping fingers and toes separately is a sign of a refined mummification, which only rich people, particularly rulers, could afford.

[26] Budge thinks that the roll was probably written in demotic, “and it is quite possible that the bishop could read this easily.”(The Life of Bishop Pisentius; p. xlviii). Butler, who incorrectly says that Budge thought that the role was written in hieroglyphic, however, believes that the roll was written in Greek characters. (Arab Conquest of Egypt; p. 86). Butler, as I believe, is more accurate.

[27] Amenti or Amentet (also Ament and Ement) is the Egyptian underworld.

[28] Ephah is a word of Egyptian origin, meaning a measure, which was used in Egypt, and was also taken by the Hebrew (see: Ex. 16:36). It was mainly used as dry measure for grains, such as wheat. In Arabic, the word is written as ‘waiba ويبة’, and is still used in Egypt. The Life of Bishop Pisentius mentions two ephahs, while The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius mentions half an ephah of wheat ‘نصف ويبة قمح’ (p. 423).

[29] The forty days of Lent. (See: The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 423).

[30] We know from the story that the punishments of the mummy’s soul were stopped as a consequence of the prayers of Pisentius for the mummy, following which, Christ allowed the mummy to be revived and to converse with the saint.

[31] In The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, Hellenes is given in the Arabic text as ‘حنفاء/ حنفين’, and O’Leary translates to ‘pagans’. (p. 424).

[32] This is reminiscent of the story of St. Shenoute with the mummy of the glassblower from Asyut, in which it cried, “Woe is me, that the womb of my mother was not my tomb before I descended to these sufferings!” See: The Life of Shenoute by Besa, translated by David N. Bell (Michigan, Cistercian Publications, 1983); p. 86.

[33] kosmokrator is a Greek word that means a ruler of this world, and which has been used in the New Testament. “In Greek literature, in Orphic hymns, etc., and in rabbinic writings, it signifies a “ruler” of the whole world, a world lord. In the NT it is used in Eph 6:12, “the world rulers (of this darkness),” RV, AV, “the rulers (of the darkness) of this world.” The context (“not against flesh and blood”) shows that not earthly potentates are indicated, but spirit powers, who, under the permissive will of God, and in consequence of human sin, exercise satanic and therefore antagonistic authority over the world in its present condition of spiritual darkness and alienation from God.” From: W. E. Vine’s New Testament Greek Grammar and Dictionary (1940).

[34] A cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the length of the forearm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger and usually equal to about 18 inches (46 centimeters) (from Merriam-Webster Dictionary). The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius gives the depth of the gulf as four thousand cubits (pp. 425-426).

[35] 2 Kings 5:25. Gehazi was the servant of Prophet Elisha.

[36] See, Hieroglyphic Vocabulary to the Book of the Dead by Sir Ernest Alfred Wallis Budge (1911); p. 41.

[37] See endnote no. 28 for the other forms of the Coptic word.

[38] The Life of Bishop Pisentius; pp. 327-328.

[39] The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 422.

[40] The Life of Apa Cyrus, the perfect monk, as told by Apa Pambo, the presbyter of the Church at Scete. See: Coptic Martyrdom etc. In the Dialect of Upper Egypt (London, 1914); pp. 381-389.

[41] NIV.

[42] KJV.

[43] Matthew 22:13. Also, see: Matthew 8:12 and Matthew 25:30. In Matthew 13:42, the wailing and gnashing of teeth is retained for those in a furnace of fire. One can say the Outer Darkness is a furnace of fire.

[44] As in The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius.

[45] As in The Life of Bishop Pisentius.

[46] See: Genesis 19, Deuteronomy 29, Isaiah 40 and 34, Ezekiel 38, and Psalm 11.

[47] Revelation 20:10, KJV.

[48] See also, Revelation 19:20, KJV.

[49] Revelation 21:8, KJV.

[50] The Life of Apa Cyrus; pp. 387-388.

[51] The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; pp. 467-477.

[52] He died on the day of 13 Epip but his final illness took several days.

[53] Ignatius of Antioch (ca. 35 – ca. 108): one of the Apostolic Fathers, disciple of St. John the Apostle, and third Bishop of Antioch. His martyrdom in Rome is famous.

[54] The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 470.

[55] The Arabic text reads: “لو نزل ملاك من السما لا بد له من عبوره ضرورة من قبل مجيئه الى الارض”.

[56] The Life of Apa Cyrus; p. 388.

[57] Sir E.A. Wallis Budge, The Book of the Saints of the Ethiopian Church (London, 1928): 8 Hamle.

[58] The Life of Bishop Pisentius; pp. 329-330.

[59] The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 427.

[60] The Life of Bishop Pisentius; p. 330.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.