Anthony Alcock has prepared a new translation of an interesting Coptic text, the Triadon. You can download the first part of his translation HERE.

Anthony Alcock has prepared a new translation of an interesting Coptic text, the Triadon. You can download the first part of his translation HERE.

Figure 1: Fayum mummy portrait of a youth from Hawara; A.D. 80-100 (in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Figure 1: Fayum mummy portrait of a youth from Hawara; A.D. 80-100 (in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

NYC).

How did he die? How did death present to him? Where did he (his soul) go after death? Where is he now? How is he doing? Is he resting in peace or is he being tormented? What will be his fate on the Last Day?

– all natural questions which Man has never stopped asking about his dead.

Man has a natural need to understand what happens at death and in the afterlife to his loved ones who have departed and ultimately to his own self. This perennial and universal question was asked by the Ancient Egyptians as it was asked later by their descendants the Copts. Our Pharaonic ancestors tried to answer the puzzle by referring to their pagan mythology; and Egyptians, once they became Christians, found a wealth of Judeo-Christian writings that can helped them in forming an idea about the destiny of Man at death and afterwards. Christian theology, in general, agrees that between death and the Last Day (Day of Judgement) when Christ returns, there is for every soul an intermediate state. Fringe Christian groups[1] believe that the soul of the dead goes into sleep in which the soul is unconscious until the day of resurrection of the bodies when Christ returns. Major Christian Churches,[2] however, believe that the soul – every soul – after death does not go into a state of coma but will be conscious; and after separating from the body (which remains in the grave to turn into dust until it is resurrected and reunited with the soul later) it will go to another place: the soul of the righteous (believer) will go to be with the Lord in Paradise; while the soul of the unrighteous (unbeliever) will go to a place of punishment may be until the Last Day. Those who go to Paradise to be with the Lord, it seems, are rare, and only great saints, such as the Virgin Mary, have been allocated that special treatment. The souls of most dead, who were believers, but had committed some sins in their lives from which they have not fully repented, will not go direct to Paradise but will be sent to Hades,[3] the abode of the dead, or the Tartarus of Hades, a deep gloomy part of Hades, according to Greek mythology, used as a dungeon, a pit, an abyss, which exists beneath the underworld, in which souls are purged and refined by tormenting and suffering to make them ready for a pass to Paradise, either before the Last Day or after it. This is what has become known in the Catholic Church as the Purgatory.[4] These souls in Hades, who undergo a process of purification, know their final place is to go to Paradise. This process can be cut short by prayers of the living community of the Church for the dead, and by succouring them through other means, such as giving alms. The intercession of saints who have departed, and presumably in Paradise with the Lord, is also influential in reducing the suffering of some of the souls in Hades.

The Copts have taken this broad understanding of death and the afterlife, which finds its basis in the Old and New Testaments. They, however, have peculiar vocabulary, concepts and imaginations of death and the afterlife, which are influenced to some extent by the mythology of their pagan forerunners. This is yet another example that there was no complete disconnect between the pagan culture of the Pharaohs and the Christian theology of the Copts, but a continuation of the old into the new when the new allows it. It is this, in addition to finding what Copts of the old really believed on Death, the Intermediate State and the Last Day – that one finds scattered in so many Coptic manuscripts – which we will try to study under this category.

Caution: This is not meant to be a theological treatise, which the author is incapable of dealing with – it is, however, a study of what Copts believed on the matter as revealed to us from what has remained of ancient manuscripts and documents.

[1] The Seventh Day Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and some evangelical Christians.

[2] Read the excellent general survey of the matter and the different positions of Christian Churches in the article by Richard P. Bucher, Where Does the Soul Go After Death? (Paradise or Soul Sleep)? Here.

[3] Hades is a Greek word that means the unseen place; the abode of the dead. When Jews and Christians translated the Bible to Greek, they used the word Hades for the Hebrew word Sheol: e.g. Acts 2:27 uses Hades for Sheol in Psalm 16:10.

[4] For the Catholic doctrine of purgatory, which is shared by Eastern Orthodox Churches, but not the Protestant Churches, go to the Catholic Encyclopedia, New Advent, Purgatory.

Figure 1: The Life of Apa Cyrus, by Pambo (Brit. Mus. MS. Oriental No. 6783. fol. 23 a).

Figure 1: The Life of Apa Cyrus, by Pambo (Brit. Mus. MS. Oriental No. 6783. fol. 23 a).

In 1914, E. A. Wallis Budge published the texts of some of the most interesting Coptic manuscripts which came under the possession of the British Museum, with their English translation. He was then Keeper of the Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities in the British Museum; and his valuable book is Coptic Martyrdom etc. In the Dialect of Upper Egypt.[1] All four published manuscripts[2] were found in Edfu (the Coptic Atbo[3] and Greek Apollinopolis Magna) in Upper Egypt, in the Monastery of Saint Mercurius and the library of the church of Saint Victor,[4] and all had been copied, from earlier manuscripts, during the second half of the tenth century and early eleventh century.[5] Budge thought the manuscripts were of “great importance for the history of Christianity in Egypt;”[6] their contents representing “the views and beliefs of the great monastic communities of Upper Egypt at the most flourishing period of their history”.[7]

One of the four manuscripts, Oriental No. 6783, was copied in 1003 AD during the Patriarchate of Philotheus (979 – 1003)[8] and the Fatimid Caliphate of Al-Hakim Bi-Amrillah (996 – 1021),[9] by a certain Victor.[10] It is a large manuscript, which includes, inter alia, The Life of Cyrus, the perfect monk, as told by Apa Pambo, the presbyter of the Church at Scete.[11]

Saint Cyrus (corrupted into Karas as consequence of Arabisation) was brother of the Emperor Theodosius I (379 – 395) and uncle of Emperors Arcadius (383 – 408) and Honorius (393 – 423). He himself tells us of his royal connection and the reason for him to renounce a life of richness and comfort and go to Egypt’s western desert to live the life of an isolated anchorite: “Cyrus is my name. I am the brother of the Emperor Theodosius, and I was reared and fed at the same table as Arcadius and Honorius. And, indeed, many, many times hath Honorius said unto me, ‘Take me with thee into the desert, and I will become a monk’; but I did not wish to take him with me, because he is a son of the Emperor. And when we saw that oppression (or, violence) had multiplied, and that the Emperors were committing sin, and that the rulers were robbing the poor, and that everyone was turning out of the straight road, and making corrupt his path before God, I rose up, and I set out and I came to this desert, and I took up my abode therein because of the multitude of my sins. May God forgive me these!”[12] There, in complete isolation in the inner desert, where no one ventured beyond to live, Apa[13] Cyrus followed a saintly life, and received no man until the eve of his death, on the 7 Epip 182 AM (1 July 466 AD),[14] when Apa Pambo,[15] the elder of the Church of Shihet[16] (the Greek Scetis, Arabic Wadi El Natrun ‘Natrun Valley’) visited him. Hitherto, only Christ visited him in his isolation, and Pambo was to witness one such visit, in which he “saw the Christ go up to that brother [Cyrus] and kiss him, mouth to mouth, even as doth a brother who hath arrived from a strange region when he meeteth his friend.”[17]

On that day, Apa Cyrus told Apa Pambo that “A great prophet and Archimandrite hath died this day, that is to say, Apa Shenoute the elder; the whole world is punished this day, for he was a very great teacher, and this day is the seventh of the month Epeph.”[18] After paying homage to Apa Shenoute, Apa Cyrus tells Apa Pambo that he is sick, a sickness he knew will end in his death, and begs him: “I beseech thee to do me the favour of praying for me until I journey over the road of fear and terror.” Astonished, Apa Pambo enquires: “My beloved father, art thou, even thou, afraid, notwithstanding all the multitude ascetic labours which thou hast performed in this world?” And Apa Cyrus responds:

“I have performed a few of the ascetic labours which God appointed for me, it is true, but how is it possible for us not to be afraid of the things which have been indicated to us by very many witnesses, that is to say, the river of fire, and the appearance before the Judge? And as for that river, everyone is bound to pass over it, whether he be a righteous man or whether he be a sinner, and it is right that thou shouldst pray on my behalf until I journey over that terrible road.

… If a man’s life upon this earth were to consist of one day only, he would not be free from sin. And, moreover, all flesh shall be purged by the fire.”[19]

And behold, it came to pass on the following day, the eighth of Epip, at the third hour,[20] that Apa Cyrus became very ill, and yielded his spirit. As Apa Pambo was weeping over Cyrus, we read, “Christ opened the door of the cell, and He came in, and He stood up by the body of the blessed Apa Cyrus, and He wept over him.”[21] The body of Apa Cyrus was then visited by a multitude of Angels, and Archangels, and Apostles, and all the righteous. One of the visitors was Saint Peter, who told Apa Pambo that Christ has taken the soul of the blessed man Apa Cyrus, and the soul of Apa Shenoute, who had died yesterday, “to the place of rest, even as it is written, ‘There are many mansions in the house of My Father.’[22]”[23] And, again, we are told that Christ Himself returned and buried the body of the blessed man, “and He became unto him a place of defence until the day of the Righteous Judgement.”[24]

__________

Here we have a story of a great man from the 5th century, whose sainthood was attested by Christ Himself, who visited him, kissed him life a friend and wept over his depaarture. When he dies, Christ takes his soul with Him to “the place of rest”, which one takes to be Paradise, a place of no fear or terror. Moreover, Christ buries Cyrus’ body, and protects it until the Last Day, when all bodies of the dead shall be resurrected, joined with their souls, to face the Judgement.

And yet, this great saint, on the last day of his life, talks of a “road of fear and terror”, a “river of fire” over which “everyone is bound to pass”, whether he be a righteous man or sinner, for no one is free of sin even if his “life upon this earth were to consist of one day only”. This river of fire seems to me to be Hades, that place of suffering many Christian thinkers thought of as intermediate status between death and the Day of Judgement. In that river of fire, all flesh (Apa Cyrus must have meant by it ‘soul’) shall be purged by the fire. There is no “soul rest” here, which some advocate in their teaching following death, when the soul stays unconscious and unperturbed until the Last Day. Furthermore, and more interestingly perhaps, Apa Cyrus is talking here about a “purgatory” for all sinners and righteous: no man shall escape the river of fire, which has the purpose of purging the souls from their sins. Is Apa Cyrus advocating a universal sort of purgatory to all humans, followed by universal salvation, along the same idea attributed to Origen? This is difficult to ascertain. Anyway, there is no doubt that he believed that the destiny of the souls of the dead can be altered by the prayers of the saintly living.

Caution: This again is not an article on theology. It just tries to bring to the forefront stories or topics that are hidden in Coptic literature, and, though they may not represent the theology of the Church of Alexandria, help us to understand how Copts saw the world and afterlife in the olden days.

[2] Oriental No. 7022, Oriental No. 6783, Oriental No. 7027, and Oriental No. 7025.

[3] Or Tbo. Sometimes it is written as tBo.

[4] Three of the manuscripts were found in the Monastery of St. Mercurius and one (Oriental No. 7025) was found in the library of the church of St. Victor.

[5] Coptic Martyrdom; Vol. I; Preface; p. xii.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Philotheus was the 63rd Coptic Patriarch. He was succeeded by the sainty Zacharias (1004 – 1032). The copying of the manuscript was finished on 23 Mesore 719 AM = 16 August 2003. Philotheus’ death is dated to 12 Hatur without giving a year; and it is possible that he died in 719 or 720 AM. If Philotheus had died on 12 Hatur 719 AM (8 November 1002), then the copying of the manuscript was finished in the period between the death of Philotheus and the ordaining of Zacharias. If, however, Philotheus died on 12 Hatur 720 AM (9 November 1003), then the manuscript copying was finished at the end of his patriarchate.

[9] In 1003 the notorious Al-Hakim was still a young boy – his persecution of the Coptic Church (1011 – 1020) was yet to come.

[10] Victor the deacon, the son of Mercurius, the son of Eponuchos, the Archdeacon of the church of Saint Mercurius the General in the town of Latopolis, or Esna, in Upper Egypt. The work was commissioned by Zacharias, a deacon and monk in the church of Saint Mercurius the General in Atbo (Apollinopolis, or Edfu), and he gave it to the shrine of the saint.

[11] Apa Pambo tells us that after the burial of the body of Apa Cyrus, he departed to his monastery in Shihet, and he wrote the life of Cyrus, placing it in the church of Shihet. This seems to be the origin of all later copies.

[12] Coptic Martyrdom; Vol. I; p. 385.

[13] ‘Apa’ is ‘father’ in Coptic.

[14] No dating in years is given in the manuscript, but as we know Saint Shenoute died in 466 AD, as most scholars now agree, the date in anno Martyri is easy to deduce.

[15] Apa Pambo, who visited Apa Cyrus, and wrote his Life is different from the greater saint who was contemporary with Saint Athanasius the Great, and is believed to have died towards the end of the 4th century.

[16] Shihet is a Coptic word that means ‘Measure of the Hearts’.

[17] Coptic Martyrdom; Volume I; p. 386.

[18] Ibid; p. 387.

[19] Ibid; pp. 387-388.

[20] 2 July 466 AD; at 9 am.

[21] Coptic Martyrdom; Vol. I; p. 388.

[22] John 14:2.

[23] Coptic Martyrdom; Vol. I; p. 388.

[24] Coptic Martyrdom; Vol. I; p. 389.

Figure 1: The sufferers in Hades get temporary rest when visited by Christ (from Dante’s Inferno).

Figure 1: The sufferers in Hades get temporary rest when visited by Christ (from Dante’s Inferno).

We have seen in our previous article “Coptic Purgatory: The Destiny of All Flesh? The Verdict of Apa Cyrus” Apa Cyrus’ vision of Hades – a “river of fire” over which everyone is bound to pass, and by which all flesh [soul] shall be purged from sin. We have learned that vision from the Life of Apa Cyrus, which was written by Apa Pambo, the presbyter of the church in Shihet in the 5th century. The story, which the British E. A. Wallis Budge found in a Coptic manuscript from the early 11th century,[1] and which he published in his Coptic Martyrdom,[2] is found repeated in other sources, such as the Synaxaria, but with some changes.

The Synaxarium (or Synaxarion) in the Coptic Church is a liturgical book containing short narratives of the lives of saints[3] arranged on the days of the year, and read in the religious services of the Church throughout the year.[4] The book, which was written in Arabic in the Middle Ages by translating earlier sources from Coptic and Greek, is available in two forms: Arabic[5] and Ethiopic.[6] [7] So, what can we find more in the Synaxaria that is not included in the Life of Apa Cyrus by Pambo? What additional information can we garner from them to help us build a more comprehensive vision of Apa Cyrus on Hades?

The Arabic Synxarium, which is used in Coptic churches in Egypt, celebrates the life of Apa Cyrus (ابا كيرس) on the 8th of Apip in a very contracted form. But still one finds in it additional information that is not available in Pambo’s Life of Cyrus: when Pambo (انبا بموا) met Cyrus, we are told, Cyrus “showed him the [rising] smokes of Hades (دخاخين الجحيم) from afar; and told him that the Lord looks at Hades every Sunday night which gives the sufferers some rest.”[8] The Ethiopian Synaxarium, which celebrates the life of the saint on the 8th of Hamle, gives a longer biography, and seems to have been taken directly from another version of Bambo’s Life of Apa Cyrus. It expands on what we have just seen in the Arabic Synaxarium:

“And at the ninth hour of the day preceding the Sabbath,[9] I [Bambo] heard a great cry, which reached to heaven, and the mountains and the hills quaked at the cry of them. And I said unto him [Cyrus], ‘O my father, what is this cry and whose are the voices which I hear?’ And he said unto me, ‘O my son, this is the cry of the sinners who are in Sheol [Hades], to whom God giveth rest from their punishment on the day of His holy Resurrection, from the ninth hour of the day preceding the Sabbath until the sun setteth on the First Day of the Week; and they praise God because it is He Who giveth them rest on the First Day of the Week.’ And I marveled exceedingly, and I praised God because He had given them rest.”

This passage tells us that the sufferers of Hades, who are passing over the “river of fire”, in order to be purified, regularly get a weekly rest period from their punishment from 3 p.m. every Friday until the sun sets on the following Sunday, in respect of Christ’s holy Resurrection. This increases our understanding of what Apa Cyrus had in mind about Hades: the sinners who suffer in the “river of fire” are not totally abandoned for the period of their purgatory punishment, but get regular periods of rest from it. This vision does not seem to be peculiar to Apa Cyrus but represents a wider viewpoint within the Coptic ascetic community of the time, as we shall see in other articles.

Caution: Again I caution the reader that these articles are not a study in Coptic theology – they are simply studies in Coptic literature to find, from our literature, how Copts in the past perceived death and Afterlife.

[1] Brit. Mus. MS. Oriental No. 6783.

[2] E. A. Wallis Budge, Coptic Martyrdom etc. In the Dialect of Upper Egypt (1914).

[3] Or exposition of feasts and fasts.

[4] Except during Pentecost.

[5] The Arabic version is what is used in the churches of Egypt. It has been translated into Latin, German and French. The latter is by René Basset (1855 – 1924) under the title Synaxaire arabe-jacobite (rédaction copte), and was published in the Patrologia Orientalis between 1904 and 1929. It is based on two Copto-Arabic manuscripts at the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris, one from the 14th century while the other is dated the 17th century. Basse’s Synaxarium is published in Arabic text at the top of the page and equivalent French text at its bottom. In 2000, the Coptic bishop, Anba Samuel published the Arabic text of Basse’s edition in four volumes under the title: السنكسار القبطى اليعقوبى لرينيه باسيه.

[6] The Ethiopian Synaxarium is a translation from a Copto-Arabic recension, and appeared towards the end of the 14th century. Its core contains stories of the saints venerated by the Egyptian Church. The Ethiopian Synaxarium is available in a French translation (published in the PO, beginning in the same year the Coptic Synaxarium was published) but also in an English translation by Sir E.A. Wallis Budge under the title The Book of the Saints of the Ethiopian Church (1928).

[8] السنكسار القبطى اليعقوبى لرينيه باسيه; Part III, p. 193 (Cairo, 2000). The English translation is mine.

[9] From Bambo’s Life of Apa Cyrus, we can find that Bambo visited Cyrus on Friday, 7 Apip 182 AM (1 July 466 AD) and on the following day, Saturday, the 8the of Apip, Cyrus died. The “ninth hour of the day preceding the Sabbath” is 3p.m. in the afternoon of Friday, 7 Apip, 182 AM (1 July 466 AD).

Figure 1: The Gebelein Man (a naturally preserved mummy from the Predynastic period, around 3500 BC, in the British Museum).

The Life of Shenoute by Besa[1] is a book that tells us a few of the miracles and marvels which God effected through the charismatic and most intriguing Coptic saint, Apa Shenoute (348 – 466 AD) the Archimandrite and abbot of the White Monastery in Akhmim (Athripe).

One of the loveliest stories in the book is that related to the corpse of a glassblower from the city of Asyut (Sioot), in Upper Egypt, who lived around the time of the birth of Jesus Christ. From what Besa, who was the disciple and successor of Shenoute, has written, we gather that the Asyutan glassblower went south to the city of Akhmim (Šmin), some sixty miles to the south, looking for work with his co-workers. But shortly after that he died, and his co-workers cast his corpse upon the mountain in the area of the White Monastery. It seems that the glassblower’s corpse, being exposed to the dry and hot weather conditions of Upper Egypt, mummified,[2] and remained where it was cast until the fifth century when Apa Shenoute used to see it around and for years wondered why it was destined to be cast there.

The identity of the corpse and the circumstances that brought it to the mountain of Akhmim is revealed when Christ once appeared to Apa Shenoute and they passed by the corpse while walking together on the mountain. There Shenoute asked Christ about the corpse, and Christ, touching the corpse with his foot, ordered it to rise up and tell Shenoute who he was and why he was cast out like this. The corpse, which was revived, told Shenoute his story. We learn from the story that when the glassblower was in Asyut or Akhmim, he heard that the Saviour had come into the world; that a woman with a little boy in her arms entered the city of El-Asmunein (Coptic Šmoun; Greek Hermopolis), which is some forty-seven miles north of Asyut.[3] This is, of course, the Holy Family’s coming to Egypt as it fled in the face of Herod’s threat to kill little Jesus.[4] Coptic tradition tells us that in El-Ashunein, the child Jesus healed crowds of sick people and performed other miracles.[5] The glassblower heard of these things, and “I resolved in my heart to go north to worship him [the Saviour] but worldly cares did not permit it”.[6]

When the glassblower is resurrected by Christ, he prostrates himself and worships the Saviour, and asks Him: “Let your mercy come upon me, and do not let me be cast into the torments again. Woe is me, that the womb of my mother was not my tomb before I descended to these sufferings!”[7] And Christ, indeed, gives him relief as he orders him to lie down “so that mercy may come upon you, and rest until the day of the true judgement”.[8] But let the reader enjoy the intriguing story himself as told by Besa:

Once, when our father apa Shenoute went into the desert, behold! The Lord Jesus appeared to him and spoke with him. As they were walking together, they came upon a corpse cast out upon the mountain. Our father apa Shenoute threw himself down and worshipped the Lord, and said to him: ‘My Lord and my God, behold, for many years I have passed by this corpse without knowing why it was destined to be cast out here’. Our Lord Jesus Christ touched the corpse with his foot and said to it: ‘Corpse, I say to you, recover yourself and rise up so that you can tell my servant Shenoute who you are, [cast out] like this’. The corpse immediately arose, just as someone would arise from sleep, and when it saw the Lord, it recognised him and worshipped him, and said to him: ‘My Lord, let your mercy come upon me!’ The saviour said to him: ‘Speak, and let my chosen one, Shenoute, know what you have done’. The corpse said: ‘What shall I say, my Lord? You know what is hidden and what is revealed, and you know what was my fate’. The Saviour said to it: ‘Nevertheless, speak, so that my servant Shenoute may hear you himself’. The corpse replied: ‘I am a glassblower from Sioout who was working with some other men. We arose and went south near Šmin so that we could work there, but after a few days had passed, I became ill and died. So because none of them was related to me by blood, they brought me here and cast me forth’. My father apa Shenoute said to him: ‘Had the Saviour come into the world at that time?’ He said: ‘Yes, he had. The news had been spread abroad and came south to us by those passing through [the area] that a woman had entered the city of Šmoun with a little boy in her arms. Everything he said came to pass: he would raise the dead, he would cast out demons, he would make the lame walk, he would make the deaf hear, he would make the dumb speak, he would cleanse lepers; in a word, he was performing every [possible] sign. When I heard these things, I resolved in my heart to go north to worship him, but [worldly] cares did not permit it.’ When the corpse had said these things, it prostrated itself and worshipped the Saviour and asked him: ‘Let your mercy come upon me, and do not let me be cast into the torments again. Woe is me, that the womb of my mother was not my tomb before I descended to these sufferings!’ The Lord said to him: ‘Inasmuch as you have been worthy to see me on earth, together with my servant apa Shenoute, I will give you a little relief. Lie down now so that mercy may come upon you, and rest until the day of the true judgement’. Straightaway the corpse lay down just as it was at first. The Saviour took the hand of our father apa Shenoute and walked with him to the cell in the desert, and they spoke of great mysteries between them. After this, [the Lord] ascended into the heavens with angels singing before him.[9]

Here we have a most beautiful story from the fifth century that tells us of one first century Asyutan glassblower’s soul that had been in torment in Hades but came face to face with Christ when Christ revived its corpse that had been cast out upon the mountain of Akhmim. The soul begged Christ for mercy, and Christ, indeed, gave it rest and relief from its torments until the Last Day.

[1] The Coptic text Coptic has been translated by David N. Bell under the title “The Life of Shenoute by Besa” (Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, Michigan, 1983).

[2] This is what is known as natural mummification.

[3] And 159 miles or so from Cairo.

[4] Matthew 2: 1-23.

[5] David N. Bell, The Life of Shenoute by Besa; n. 92; p. 111.

[6] Ibid; p. 86.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid; pp. 85-86.

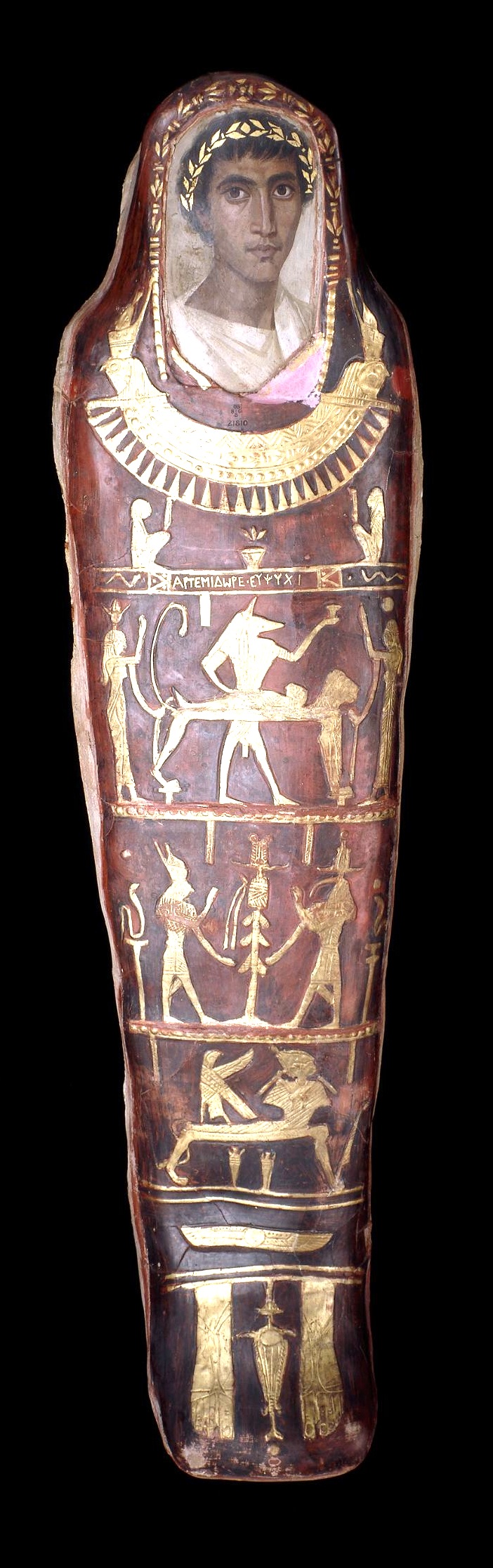

Figure 1: The Mummy of Artemidorus, AD 100-120 (In the British Museum).

The Life of Bishop Pisentius is very important in many ways not least because it sheds some light on what Copts of the Classic Period,[1] at least, thought of death and afterlife. Saint Pisentius[2] (548 – 632 AD) was selected bishop of Coptos,[3] in deep Upper Egypt, in AD 599, and remained bishop there until his death.[4] The Life of Bishop Pisentius is written in the 7th Century by his disciple, John the Elder, but there are other recensions where one finds the names of Moses and Tawudoros (Theodore) as authors too.[5] We have it in Coptic Sahidic, Coptic Bohairic (Memphitic), Arabic and Ethiopic versions;[6] and some of these were published in English:

- The Sahidic version: This was translated in 1913 by E. A. Wallis Budge in his Coptic Apocrypha in the Dialect of Upper Egypt under the title The Life of Bishop Pisentius, by John the Elder.[7] This manuscript (Brit. Mus. MS. Oriental No. 7026) dates to AD 985. In his book, Budge included an excellent Introduction on Bishop Pisentius.[8]

- The Bohairic (Memphitic) version: This was edited by E. Amélineau in 1889,[9] and is attributed to John the Presbyter and Moses, Bishop of Coptos (he succeeded Pisentius). This version, unlike the Sahidic version, contains the story of Pisentius’ conversation with the mummy, the story that interests us here. Budge translated the story, and added it as an appendix to his translation of the Sahidic version.[10] It is the story in this Bohairic version which we use here under the title The Life of Bishop Pisentius.

- The Arabic version: There are many Arabic versions. In 1930, DeLacy E. O’Leary used two Arabic manuscripts in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Arabe 4785 and Arabe 4794), which he didn’t date, to publish his The Arabic life of S. Pisentius,[11] and he says both manuscripts contain the miracle of the saint’s “converse with the dead”.[12] The book includes fifty six wonders of the saint, and it is The Thirty Two Wonder which deals with Pisentius’ conversation with the mummy.[13]

Saint Pisentius was bishop of Coptos at the time of the Persian invasion of Egypt, in AD 619, when Khosraw II Pevez took Egypt from the Byzantines. This third Persian occupation of Egypt (619-629 AD)[14] lasted for only ten years, and ended when Heraclius I wrestled Egypt back from the Persians. Once Bishop Pisentius got the news of the approaching Persians, he wrote a pastoral letter to all his diocese in which he said, “Because of our sins God has abandoned us; he has delivered us to the nations without mercy;”[15] and he, together with his disciple and biographer John, fled some 23 miles south to the mountain of Tjîmi[16] (called Shama شامة in Arabic manuscripts)[17] in Western Thebes (Luxor), where he stayed in retreat for ten years,[18] “praying night and day that God would save the people from bondage to those cruel nations.”[19] Only John knew his hiding place, and he used to take him a supply of food and drink each Sabbath day.[20]

In the recesses of that mountain, Pisentius found a tomb in which he took refuge. It possessed “a large hall about 80 feet square, and its roof was supported by six pillars. This hall was made probably under one of the kings of the New Empire, and had been turned at a much later period, perhaps in one of the early centuries of the Christian era, into a common burial-place for the mummies of people of all classes. At all events, when John was taken there by his master the hall contained many mummified bodies, and the air was heavy with the odour of funerary spices. Pisentius and his disciple opened some of the coffins, which were very large, with much decorated inner coffins. One mummy was swathed in silk, and must therefore have belonged to the third or fourth century of our era. As John was about to leave Pisentius he noticed on one of the pillars a small roll of parchment, and when Pisentius had opened it he read therein the names of all the people who had been buried in that tomb. The roll was probably written in demotic, and it is quite possible that the bishop could read this easily.”[21]

In that Pharaonic hall, used as little necropolis for some mummified dead from the Roman period, Pisentius had a curious encounter and intriguing conversation with a mummy, which was heard by John when he returned the following Saturday with water and food supply for the week, and later documented it in his book. We know that the mummy belonged to a man from Erment;[22] and although we are not given his name, his parents’ names we are given as Agricolaos and Eustathia, and that they were Hellenes. Furthermore, we are told that the family worshipped Poseidon, the Greek God of the Sea. That encounter with that mummy reveals a great deal of what Copts of that age thought of death and afterlife.

Let us read together that fascinating story in The Life of Bishop Pisentius as it was told in the Bohairic (Memphitic) version, and which was published by E. A. Wallis Budge:[23]

And it came to pass on a day whilst my father was still with me in the mountain of Tjîmi that my father said unto me, ‘John, my son, rise up, follow me, and I will shew thee the place wherein I repose and pray, so that thou mayest visit me every Sabbath and bring me a little food, and a little water to drink wherewith to support my body.’ And my father rose up, and walked before me, and he was meditating on the Holy Scriptures of the Spirit of God. And when we had walked about three miles, at least so the distance appeared to me, we came to a path which was in the form of a door which was wide open. And when we had gone inside that place, we found that it had the appearance of being hewn out of the rock, and there were six pilasters rising up against the rock. It was fifty-two cubits in length, it was four-cornered, and its height was in proportion [to its length and breadth]. There was a large number of bodies which had been mummified in it, and if thou wast merely to walk outside that place thou wouldst be able to smell the ‘sweet smell’ (i.e. spices), which emanated from these bodies. And we took the coffins, we piled them up one on top of the other — now the place was very spacious — ……..[24] The swathings wherein the first mummy, which was near the door, was wrapped, were of the silk of kings. And his stature was large, and the fingers of his hands and his toes were bandaged separately.[25] And my father said, ‘How many years ago is it since these [people] died? And from what nomes do they come?’ And I said unto him, ‘It is God [only] Who knoweth.’ And my father said unto me, ‘Get thee gone, my son. Sit in thy monastery, take heed to thyself, this world is a thing of vanity, and we may be removed from it at any moment. Take care for thy wretched state. Continue thy fastings scrupulously. Pray thy prayers regularly hour by hour, even as I have taught thee, and do not come here except on the Sabbath.’ And when he had said these things unto me, I was about to come forth from his presence, when looking carefully on one of the pilasters, I found a small parchment roll. And when my father had unrolled it, he read it, and he found written therein the names of all the people who were buried in that place; he gave it to me and I put it down in its place.[26]

And I saluted my father, and I came away from him, and I walked on, and as he shewed me the way he said unto me, ‘Be thou diligent in the work of God so that He may shew mercy unto thy wretched soul. Thou seest these mummies; needs must that every one shall become like unto them. Some are now in Amenti,[27] — those whose sins are many, others are in the Outer Darkness, and others are in pits and basins which are filled with fire, and others are in the Amenti which is below, and others are in the river of fire, where up to this present they have found no rest. Similarly others are in a place of rest, according to their good works. When a man goeth forth from this world, what is past is past.’ And when he had said these things unto me, he said, ‘Pray for me also, my son, until I see thee [again].’ So I came to my abode, and I stayed there, and I did according to the command of my holy father, Abba Pisentius.

And on the first Sabbath I filled my water-pot with water, and [I took] a little soft wheat, according to the amount which he was likely to eat, according to his command (he gave [me] the order [to bring] two ephahs[28] which he distributed over the forty days),[29] and he took the measure and measured it, saying, ‘When thou comest on the Saturday bring me this measure [full] with the water.’ So I took the pitcher of water and the little soft wheat, and I went to the place wherein he reposed and prayed. And when I had come in to the abode I heard some one weeping and beseeching my father in great tribulation, saying, ‘I beseech thee, O my lord and father, to pray unto the Lord for me so that I may be delivered from these punishments, and that they may never take hold of me again, for I have suffered exceedingly.’[30] And I thought that it was a man who was speaking with my father, for the place was in darkness. And I sat down, and I perceived the voice of my father, with whom a mummy was speaking. And my father said unto the mummy, ‘What nome dost thou belong to?’ And the mummy said, ‘I am from the city of Ermant.’ My father said unto him, ‘Who is thy father?’ He said, ‘My father was Agrikolaos and my mother was Eustathia.’ My father said unto him, ‘Whom did they worship?’ And he said, ‘They worshipped him who is in the waters, that is to say Poseidôn.’ My father said unto him, ‘Didst thou not hear before thou didst die that Christ had come into the world?’ He said, ‘No, my father. My parents were Hellenes,[31] and I followed their life. Woe, woe is me that I was born into the world! Why did not the womb of my mother become my grave?[32] And it came to pass that when I came into the straits of death, the first who came round about me were the beings “Kosmokrator”,[33] and they declared all the evil things which I had done, and they said unto me, “Let them come now and deliver thee from the punishments wherein they will cast thee.” There were iron knives in their hands, and iron daggers with pointed ends as sharp as spear points, and they drove these into my sides, and they gnashed their teeth furiously against me. After a little time my eyes were opened, and I saw death suspended in the air in many forms. And straightway the Angels of cruelty snatched my wretched soul from my body, and they bound it under the form of a black horse, and dragged me to Ement (Amenti). O woe be unto every sinner like myself who is born into the world! O my lord and father, they delivered me over into the hands of a large number of tormentors who were merciless, each one of whom had a different form. O how many were the wild beasts which I saw on the road! O how many were the Powers which tortured me! When they had cast me into the outer darkness I saw a great gulf, which was more than a hundred cubits deep,[34] and it was filled with reptiles, and each one of these had seven heads, and all their bodies were covered as it were with scorpions. And there was another mighty serpent in that place, and it was exceedingly large, and it was a terrible sight to behold; and it had in its mouth teeth which were like unto pegs of iron. And one laid hold of me and cast me into the mouth of that Worm, which never stopped devouring; all the wild beasts were gathered together about him at all times, and when he filled his mouth all the wild beasts which were round about him filled their mouths with him.’

My father said unto him, ‘From the time when thou didst die until this day, hath no rest been given unto thee, or hast thou not been permitted to enjoy any respite from thy suffering?’ And the mummy said, ‘Yes, my father, mercy is shewn unto those who are suffering torments each Sabbath and each Lord’s Day. When the Lord’s Day cometh to an end, they cast us again into our tortures in order to make us to forget the years which we lived in the world. Afterwards, when we have forgotten the misery of this kind of torture, they cast us into another which is far more severe. When thou didst pray for me, straightway the Lord commanded those who were flogging me, and they removed from my mouth the iron gag which they had placed there, and they released me, and I came to thee. Behold, I have told you the conditions under which I subsist. O my lord and father, pray for me, so that they may give me a little rest, and that they may not take me back into that place again.’ And my father said unto him, ‘The Lord is compassionate, and He will shew mercy unto thee. Go back and lie down until the Day of the General Resurrection, wherein every man shall rise up, and thou thyself shalt rise with them.’ God is my witness, O my brethren, I saw the mummy with my own eyes lie down again in its place, as it was before. And having seen these things I marvelled greatly, and I gave glory unto God. And I cried out in front of me, according to rule, ‘Bless me,’ and then I went in and kissed his hands and his feet. He said unto me, ‘John, hadst thou been here a long time? Didst thou not see somebody or hear somebody talking to me?’ And I said, ‘No, my father.’ He said unto me, ‘Thou speakest falsehood, just as did Gehazi when he uttered falsehood to the prophet, saying, “Thy servant went no whither.”[35] But since thou hast seen or heard, if thou tellest any man during my lifetime thou shalt be cast forth (i.e. excommunicated).’ And I have observed the order, and I have never dared to repeat it to this very day.

Here we have an extraordinary encounter of the seventh century saint, Bishop Pisentius of Coptos, with a Hellene mummy that was lodged, with other mummies, in a Pharaonic hall in the mountain of Tjîmi, in Western Thebes, sometime in the third or fourth century. The encounter was witnessed by John, Pisentius’ disciple, and he recorded it after the death of the bishop in AD 632. It sheds, as the reader has seen, important light on the Coptic perceptions and beliefs of the destiny of man at death and then after it. We can summarise these in the following:

1. At man’s death, his soul departs from his body; it does not sleep or go into coma until the Last Day. Furthermore, all souls are immortal and accountable to God.

2. Following death, all souls go to the underworld, to spend an intermediate phase of their existence until the Judgement Day. This underworld, the Copts called Amenti, which is an ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic word and means “the hidden place, or land, the West, the abode of departed spirits, the name of the first division of the Other World”.[36] The equivalent word in Greek is Hades; in Hebrew Sheol; in English Hell; and in Arabic الجحيم.[37]

3. Amenti is composed of different places to accommodate souls with different degrees of sin. These places, or stations, are not immediately clear in The Life of Bishop Pisentius, most probably as a result of some careless copyist. In it Pisentius says to his disciple John:

Thou seest these mummies; needs must that every one shall become like unto them. Some are now in Amenti, — those whose sins are many, others are in the Outer Darkness, and others are in pits and basins which are filled with fire, and others are in the Amenti which is below, and others are in the river of fire, where up to this present they have found no rest. Similarly others are in a place of rest, according to their good works.[38]

The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, on the other hand, gives it a bit different:

Thou hast seen, O my son, all these dead cast aside to warn us that we shall be like them. Some of them are those who are gnashing their teeth, others are in the outer darkness, others are in torment and in the pit full of fire and brimstone, their abode in the lowest hell, and some of them are in the river of fire and have never been able to get out to this present time, and some of them are in places of repose because of their works.[39]

By comparing the two versions, and by resort to relevant Biblical texts, one can come to a clearer understanding: It seems that the Copts had in mind four stations in Amente:

a. The “Place of Rest”, “Places of Repose”, which some souls occupy because of their [good] works while in the body on the earth.

b. The “River of Fire” which some sinful souls must cross in order to be purified, and be able to be admitted to the “Place of Rest” at some stage. We have seen this “River of Fire” in The Life of Apa Cyrus.[40] The “River of Fire”[41] (or the “Fiery Stream”[42]) is mentioned in Daniel 7:10, but not in the way intended in The Life of Bishop Pisentius, The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, or The Life of Apa Cyrus.

c. The “Outer Darkness”, into which the soul of our mummy was cast, is where those gnashing their teeth, a sign of pain, sorrow and grief for realising one’s own sins in full, are thrown. This “Outer Darkness” is mentioned, associated with weeping and gnashing of teeth, in so many verses in the Gospel according to St. Matthew, such as: “Then said the king to the servants, Bind him hand and foot, and take him away, and cast him into outer darkness; there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”[43]

d. The “Pit full of Fire and Brimstone (Sulphur)”,[44] or “”Pits and Basins which are filled with Fire”,[45] exist at the bottom of Amenti, in the lowest hell. This seems to be retained for the devil and the ungodly who deserve eternal punishment. Both Old[46] and New Testaments refer to it, particularly in the Book of Revelation, such as: “And the devil that deceived them was cast into the lake of fire and brimstone, where the beast and the false prophet are, and shall be tormented day and night for ever and ever;”[47] [48]and: “But the fearful, and unbelieving, and the abominable, and murderers, and whoremongers, and sorcerers, and idolaters, and all liars, shall have their part in the lake which burneth with fire and brimstone: which is the second death.”[49]

4. The “River of Fire” is a fascinating station of Amente according to the Coptic concept. We quote here the relevant piece in The Life of Apa Cyrus:

I [Cyrus] have performed a few of the ascetic labours which God appointed for me, it is true, but how is it possible for us not to be afraid of the things which have been indicated to us by very many witnesses, that is to say, the river of fire, and the appearance before the Judge? And as for that river, everyone is bound to pass over it, whether he be a righteous man or whether he be a sinner, and it is right that thou shouldst pray on my behalf until I journey over that terrible road.

… If a man’s life upon this earth were to consist of one day only, he would not be free from sin. And, moreover, all flesh shall be purged by the fire.[50]

We find a similar passage in The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius under the Fifty Three Wonder:[51] as Pisentius approached his death,[52]John tells us:

[Apa Pisentius] prayed and offered supplication and said: ‘O martyr of Christ, Ignatius,[53] come to me and strengthen my faith: bring the crown which does not decay, with the rest of the athletes. Be with me until I reach the river of fire which flows before the just judge, where there is great and very dreadful fear.’ And I said to him: ‘O my father, after the penances thou hast endured in the world, and fastings, and prayers, and fatigues, and long vigils, dost thou fear the river of fire?’ And the blessed one answered and said: ‘Who is safe from crossing the fiery river? — I say to thee that if an angel came from heaven he would not escape its crossing before coming to the earth.’ And he informed me: ‘I shall cross it on the evening of the thirteenth day of the month Abib.’[54]

Now, I don’t think O’Leary’s translation of the Arabic text is entirely correct. His “Who is safe from crossing the fiery river? — I say to thee that if an angel came from heaven he would not escape its crossing before coming to the earth” must be ““Who is safe from crossing the fiery river? — I say to thee that if an angel came from heaven he must cross it in view of his coming to the earth.”[55] This gives the same meaning that Apa Cyrus wanted to convey: that everyone had to pass over the “River of Fire”, whether he is a righteous man or whether he is a sinner; that no man is free of sin even if his life on earth were to consist of only one day. Apa Pisentius reinforces that by saying even angels if they came to, and lived on, the earth will not be free from sin, and they too must pass through that fire for purification. This, in my opinion, does not mean that, in the Coptic mind, righteous men will definitely pass through this “River of Fire” – what it means is that no one, however saintly, deserves to go to the Place of Rest or Paradise by right: man can only do that through the grace of God. Both Apa Cyrus and Apa Pisentius, in their humility, showed this understanding, and Christ, we are told, showed his mercy to them: we do not know what happened to Apa Pisentius at his death, as his biography doesn’t tell us; however, we know from the Life of Apa Cyrus that Christ has taken the souls of Apa Cyrus and Apa Shenoute, who died a day earlier, to “the place of rest”.[56]

Apa Cyrus says, “All flesh shall be purged by fire”. This may give the impression that all souls will pass through the “River of Fire”, and get their sins washed away through suffering, and so will eventually be saved – i.e. a purgatory for all and a universal salvation. However, read in conjunction with The Life of Bishop Pisentius, one tends to think that only sinners in the “outer Darkness” may be able to do so – those in the “Pit full of Fire and Brimstone”, or the devil and the “ungodly” referred to in Revelation 19-21, will not.

5. The regular respite period which we have seen in The Ethiopian Synaxarium when it talks about Apa Cyrus is again emphasised here, however inadequately. In The Ethiopian Synaxarium we are told that those sinners who are being tormented in Amente get rest from their punishments “on the day of His holy Resurrection, from the ninth hour of the day preceding the Sabbath until the sun setteth on the First Day of the Week”; that is from 3 p.m. on Friday until sunset on Sunday.[57] In The Life of Bishop Pisentius, sufferers are shown mercy “each Sabbath and each Lord’s Day”[58], and in The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, the relief given is “on the night of Sunday, because it is the resurrection of Christ,” “from the ninth hour of the sabbath until the end of Sunday.”[59]

6. Copts have always prayed for their reposed in private and public prayer: they believe that prayer of the faithful on earth does help those departed souls in Amente – and this seems to be an old tradition. We have seen that once Pisentius prayed for the mummy, straightway “the Lord commanded those who were flogging me, and they removed from my mouth the iron gag which they had placed there, and they released me, and I came to thee.”[60] The soul knew of the power of prayer, and so it beseeched Pisentius: “O my lord and father, pray for me, so that they may give me a little rest, and that they may not take me back into that place again.”[61] And Pisentius, having faith in Christ’s mercy, says to the mummy, “The Lord is compassionate, and He will shew mercy unto thee. Go back and lie down until the Day of the General Resurrection, wherein every man shall rise up, and thou thyself shalt rise with them.”[62]

The description by the mummy of his illness that led to his death, the arrival of death, the dragging of his soul to Amente and its casting in the Outer Darkness, and the torments he has received in it, all make excellent figurative language. To take it literally in physical terms, rather than as a metaphor for the agonising pain that a sinful soul meets at and after death, is difficult. It is, however, very effective in bringing to listeners and readers the seriousness of the consequences of their living in sin. The Coptic Amente or underworld may be fearful and a place for suffering and pain; it, however, is also a place where many dead find their rest in peace, and many others experience temporary suffering as their souls are being purified, always being aware of their final salvation – in other words, side by side with sadness and despair exist joy and hope.

[1] An intelligent periodification of Coptic history has not been made yet, but I use “Coptic Classic Period” here to mean the history of the Copts from the introduction of Christianity to Egypt in the first century until the Arab occupation of Egypt in the seventh century. This period can be subdivided into several distinct periods.

[2] Also written Pisentios, Pisuntios and Pisentius; and in Arabic بيسنتاوس, بسنتاؤس, بسنتيوس, بسنتاووس, بسندة and بسنتى .

[3] Also Qift (قفط in Arabic). It is a city in the Governorate of Qena, some 300 miles south of Cairo, and 23 miles north of Luxor.

[4] For these dates, see: تاريخ المسيحية والرهبنة وآثارهما في أبروشيتي نقادة وقوص وإسنا والأقصر وأرمنت (Tārīkh al-Masīḥīyah wa-al-rahbanah wa-āthārihimā fī abrūshīyatay Naqādah wa-Qūṣ, wa-Isnā wa-al-Uqṣur wa-Armant) by Nabīh Kāmil Dāwud and ʻĀdil Fakhrī (Cairo, Institute of St. Mark for Studies in Coptic History, 2008); p.136.

[5] Ibid.; pp. 136-140.

[6] Ibid.

[7] E. A. Wallis Budge in his Coptic Apocrypha in the Dialect of Upper Egypt (London, 1013); pp. 258-334. The Coptic Sahidic text, Budge included in pp. 75-127.

[8] Ibid.; pp. xli-l.

[9] “Un évêque de Keft au VIIe siècle”, Mémoires présentes et lus à l’Institut égyptien II (Paris, 1889); introd., pp.261-332; text and trans., pp. 333-423.

[10] Coptic Apocrypha; pp. 322-330 include this story and two other stories which are not available in the Sahidic version.

[11] DeLacy E. O’Leary, The Arabic life of S[aint] Pisentius : according to the text of the 2 ms. Paris Bib. Nat. arabe 4785 and arabe 4794 in the Patrologia Orientalis; Tome 22, Fasc. 3, No. 109 (Paris, Firmin-Didot, 1930); introd., pp. 317-321; text and trans., pp. 322-488.

[12] In Arabe 4785, in 176.6; and in Arabe 4794, in 136.a-1 11.a. But it seems that, in his book, O’Leary uses Arab 4785 only in his translation of Miracle 32.

[13] Ibid., pp. 419-429.

[14] This invasion was undertaken by the Sassanid king, Khosraw II Parvez. Two previous Persian invasions occurred under the Archaemenids: the First Persian Period (525-402 BC) was inaugurated by Cambyses II who ended the 26th Dynasty, and established the 27th Dynasty (the 1st Persian Dynasty). The Second Persian Period (343-332 BC), which was established by Artaxerxes III, who conquered Egypt for a brief period, and founded the 31st Dynasty. This dynasty was ended by Alexander the Great.

[15] A. Butler: Arab Conquest of Egypt And The last Thirty Years of the Roman Dominion (Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 1902; ed. 1998); p. 85. This blaming of one’s sins for disasters was a common Christian explanation of historical events during the Byzantine times.

[16] Djîmé or Gemi.

[17] We know that Saint Pisentius started his monkish life in the same mountain. تاريخ المسيحية والرهبنة وآثارهما; p. 136.

[18] We know he stayed in hiding from the Persians for ten years (i.e., the whole ten years of the Persian rule) from The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 462.

[19] Arab Conquest of Egypt; p. 85.

[20] John stayed in a nearby monastery, most probably the Monastery of St. Phoebammon (Abe Fam) the Soldier (his martyrdom is celebrated in the Synaxarium on 27 Toba), which was close bye (west of Luxor and the Valley of the Queens by some 5 miles). تاريخ المسيحية والرهبنة وآثارهما; p. 314.

[21] Coptic Apocrypha; Introduction; p. xlviii.

[22] Erment (the modern town of Armant; Greek, Hermonthis), which is located about 8 miles south of Thebes. This is also the town from which Pisentius’ parents came (تاريخ المسيحية والرهبنة وآثارهما; 153).

[23] I have taken out words written in Coptic.

[24] Budge leaves several words without translation as he says their exact meaning is not clear to him (footnote no. 1 on p. 327). Looking at the Arabic text of the manuscript Arabe 4785, in Paris, which O’Leary published in his The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, one can see that the Arabic equivalent for the missing words is “ووجدنا الأرض التي كانت عليها الأموات وقد لانت كطين الفاخوري المعجون”. O’Leary translates these as “And we found the earth which was on the mummies to be soft like potter’s clay” (p. 421). I think the right translation should change the ‘on’ preposition used by O’Leary to ‘under’.

[25] Wrapping fingers and toes separately is a sign of a refined mummification, which only rich people, particularly rulers, could afford.

[26] Budge thinks that the roll was probably written in demotic, “and it is quite possible that the bishop could read this easily.”(The Life of Bishop Pisentius; p. xlviii). Butler, who incorrectly says that Budge thought that the role was written in hieroglyphic, however, believes that the roll was written in Greek characters. (Arab Conquest of Egypt; p. 86). Butler, as I believe, is more accurate.

[27] Amenti or Amentet (also Ament and Ement) is the Egyptian underworld.

[28] Ephah is a word of Egyptian origin, meaning a measure, which was used in Egypt, and was also taken by the Hebrew (see: Ex. 16:36). It was mainly used as dry measure for grains, such as wheat. In Arabic, the word is written as ‘waiba ويبة’, and is still used in Egypt. The Life of Bishop Pisentius mentions two ephahs, while The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius mentions half an ephah of wheat ‘نصف ويبة قمح’ (p. 423).

[29] The forty days of Lent. (See: The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 423).

[30] We know from the story that the punishments of the mummy’s soul were stopped as a consequence of the prayers of Pisentius for the mummy, following which, Christ allowed the mummy to be revived and to converse with the saint.

[31] In The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius, Hellenes is given in the Arabic text as ‘حنفاء/ حنفين’, and O’Leary translates to ‘pagans’. (p. 424).

[32] This is reminiscent of the story of St. Shenoute with the mummy of the glassblower from Asyut, in which it cried, “Woe is me, that the womb of my mother was not my tomb before I descended to these sufferings!” See: The Life of Shenoute by Besa, translated by David N. Bell (Michigan, Cistercian Publications, 1983); p. 86.

[33] kosmokrator is a Greek word that means a ruler of this world, and which has been used in the New Testament. “In Greek literature, in Orphic hymns, etc., and in rabbinic writings, it signifies a “ruler” of the whole world, a world lord. In the NT it is used in Eph 6:12, “the world rulers (of this darkness),” RV, AV, “the rulers (of the darkness) of this world.” The context (“not against flesh and blood”) shows that not earthly potentates are indicated, but spirit powers, who, under the permissive will of God, and in consequence of human sin, exercise satanic and therefore antagonistic authority over the world in its present condition of spiritual darkness and alienation from God.” From: W. E. Vine’s New Testament Greek Grammar and Dictionary (1940).

[34] A cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the length of the forearm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger and usually equal to about 18 inches (46 centimeters) (from Merriam-Webster Dictionary). The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius gives the depth of the gulf as four thousand cubits (pp. 425-426).

[35] 2 Kings 5:25. Gehazi was the servant of Prophet Elisha.

[36] See, Hieroglyphic Vocabulary to the Book of the Dead by Sir Ernest Alfred Wallis Budge (1911); p. 41.

[37] See endnote no. 28 for the other forms of the Coptic word.

[38] The Life of Bishop Pisentius; pp. 327-328.

[39] The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 422.

[40] The Life of Apa Cyrus, the perfect monk, as told by Apa Pambo, the presbyter of the Church at Scete. See: Coptic Martyrdom etc. In the Dialect of Upper Egypt (London, 1914); pp. 381-389.

[41] NIV.

[42] KJV.

[43] Matthew 22:13. Also, see: Matthew 8:12 and Matthew 25:30. In Matthew 13:42, the wailing and gnashing of teeth is retained for those in a furnace of fire. One can say the Outer Darkness is a furnace of fire.

[44] As in The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius.

[45] As in The Life of Bishop Pisentius.

[46] See: Genesis 19, Deuteronomy 29, Isaiah 40 and 34, Ezekiel 38, and Psalm 11.

[47] Revelation 20:10, KJV.

[48] See also, Revelation 19:20, KJV.

[49] Revelation 21:8, KJV.

[50] The Life of Apa Cyrus; pp. 387-388.

[51] The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; pp. 467-477.

[52] He died on the day of 13 Epip but his final illness took several days.

[53] Ignatius of Antioch (ca. 35 – ca. 108): one of the Apostolic Fathers, disciple of St. John the Apostle, and third Bishop of Antioch. His martyrdom in Rome is famous.

[54] The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 470.

[55] The Arabic text reads: “لو نزل ملاك من السما لا بد له من عبوره ضرورة من قبل مجيئه الى الارض”.

[56] The Life of Apa Cyrus; p. 388.

[57] Sir E.A. Wallis Budge, The Book of the Saints of the Ethiopian Church (London, 1928): 8 Hamle.

[58] The Life of Bishop Pisentius; pp. 329-330.

[59] The Arabic Life of S. Pisentius; p. 427.

[60] The Life of Bishop Pisentius; p. 330.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

Figure 1: Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge by Bassano, in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

The British Orientalist, Egyptologist and Coptologist Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge, or simply E. A. Wallis Budge, (1857 – 1934), is one of the great English scholars to home Copts and those interested in the study of Coptic culture, language and theology are very much indebted. It was during his job as keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities in the British Museum, in London, towards the end of the nineteenth and at the beginning of the twentieth centuries that his scholarly work was most useful to Coptic studies.

Budge was an expert in Sahidic Coptic, or what he better describes as Upper Egyptian Dialect, the dialect in which great Copts like St. Shenoute and St. Pisentius spoke and wrote. And it is this scholarly knowledge in this dialect, together with his work at the British Museum, which allowed him to undertake the great work of publishing, translating and editing what he calls the “Edfû Manuscripts”, and what others call the “Edfû Codices” – this treasure which is invaluable in the study of Coptic culture, traditions, customs and folklore; Coptic Christianity; and what Copts thought and had in mind, during that time, about the world, religion, justice, love, death, afterlife, Emente, Paradise, sin, evil, goodness, eschatology, angelology, demonology, philosophy, hermitic life, coenobium, history, etc. This Coptic gem, which he published in five large volumes, he tells us, “contain all the principal texts from the series of parchments and paper volumes that originally formed parts of the libraries of the monasteries and churches of Edfû and Asnâ[1], and are now in the British Museum.”[2] And he adds: “Thirteen of these were acquired for the Trustees [of the British Museum] by myself in 1907-8, and the remainder were purchased from Mr. Rustafjaell.[3]”[4]

The five great volumes, and their publication dates, are the following (you can click on them to access the wealth of their material):

[1] Asna (or Esna; Latopolis in Greek) and Edfu (or Edfu or Idfu; Apollinopolis in Greek) are two ancient Egyptian cities on the western side of the Nile. They are both located in deep Upper Egypt between Luxor in the north and Aswan in the south; and although they are rich with Pharaonic, Greek, Roman and Coptic antiquities they are rarely visited by tourists as most don’t venture beyond Luxor.

[2] Miscellaneous Coptic texts in the dialect of Upper Egypt (1915); p. xxiv.

[3] Robert de Rustafjaell (c. 1876 – 1976), an American archaeologist and collector, mainly of Coptological and Egyptological material. He is also known as Col. Prince Roman Orbeliani.

[4] Miscellaneous Coptic texts in the dialect of Upper Egypt (1915); p. xxiv.

Figure 1: The Coptic title of Brit. Mus. Oriental 5000, which means The Psalter Book.

Figure 1: The Coptic title of Brit. Mus. Oriental 5000, which means The Psalter Book.

Figure 2: The title page of Budge’s book (1898). Only 250 copies were printed.

Figure 2: The title page of Budge’s book (1898). Only 250 copies were printed.

Figure 3: Sir Earnest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (1857-1934), English scholar, Egyptologist, Orientalist and Sometime keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities in the British Museum.

Figure 3: Sir Earnest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (1857-1934), English scholar, Egyptologist, Orientalist and Sometime keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities in the British Museum.

In 1898, E. A. Wallis Budge edited a book under the title, The Earliest Known Coptic Psalter: The text, in the dialect of Upper Egypt, edited from the unique papyrus codex Oriental 5000 in the British museum, which the reader can access it here.[1] Budge was right in claiming at that time that it was the earliest known Coptic psalter; but as we shall know from the next article, it isn’t. However, Budges. Coptic psaltery remains the earliest known complete Coptic psaltery in the dialect of Upper Egypt (or Sahidic), and that is why I stressed that in the title of this article.

Budge estimates the date of the original manuscript to the end of the sixth or the beginning of the seventh century; i. e. before the Arab occupation of Egypt, or what I prefer to call the Coptic Classic Period. It underwent a few repairs, however, in the eleventh or twelfth century. The manuscript, which had been previously in the British Museum (Brit. Mus. MS. Oriental 5000), is now in the British Library; and it forms part of the Edfû Manuscripts (or Edfû Codices). Budge describes the circumstances of the great finds (it was found with another important manuscript: Brit. Mus. MS. Oriental 5001):

About two years ago[2] whilst certain Egyptian peasants were digging up and carrying away the light soil, which is so much valued for “top-dressing” by the farmers, from the ruins of an ancient Coptic church and monastery in Upper Egypt, their tools struck upon a rectangular slab of stone. An examination showed that this slab formed the cover of a stone box or coffer which had been firmly fastened in the ground, and when, after some difficulty, it was removed, a parcel of books, carefully wrapped in coarse linen cloth, was found lying beneath it. The books were two in number and, though written up on papyrus, they were found to be bound in stout leather covers, after the manner of European books in general. That these volumes had lain in the box for several hundreds of years there is no possibility of doubting, but there is no way of ascertaining the exact period when they were first placed in it. It is the opinion of some that the church and monastery which once stood upon the site where the books were found had been in ruins for some centuries, and the general appearance of the place supports this view. There is no reason for supposing that the books were buried along with the body of any ecclesiastical official or monk, for it is certain that they had been expressly written for use in the church of the monastery, and that they were not the private property of any member of it. It would seem that at some period of trouble or persecution an official of the church carefully prepared the box in the event of its ever being necessary to hide books, and that when the need arose he wrapped these volumes in linen with the greatest care, and laid them in it. Their wonderful state of preservation testifies to the wisdom of the choice of a hiding place and the thoroughness with which he carried out the self-appointed task. That they were believed by him to be books of no ordinary kind is evident, and though it is early yet to pronounce a definite opinion upon the value of their contents, it seems clear that the discovery of a complete copy of the Psalter in the dialect of Upper Egypt, and of a volume containing ten complete Homilies by Fathers of the Monophysite Church[3]—for such in fact are the contents of the book—bids fair to rank among the greatest of the great “finds” which have been made in Egypt during the last few years. [Preface; pp. vii, viii]

[2] The book was published in 1898 but Budge wrote his Preface in 1897.

[3] Budge later published these homilies in his book, COPTIC HOMILIES IN THE DIALECT OF UPPER EGYPT; edited from the papyrus codex Oriental 5001 in the British museum (1910).

Figure 1: The Mudil Codex (The Coptic Psalter in the dialect of Middle Egypt) – the oldest Coptic psalter ever discovered. It is kept in the Coptic Museum in Old (Coptic) Cairo.

In a previous article, we have seen the oldest complete Coptic psalter in the Upper Egypt (Sahidic) dialect, which was edited by E. A. Wallis Budge, and published in London in 1898. It formed part of the Edfû Manuscript (or Edfû Codices), and goes back to the end of the sixth or seventh century. Now, it is time to speak about the oldest Coptic psalter ever – what is called the Mudil Codex, which is written in Middle Egypt (Oxyrhychitic) dialect, and dates from the fourth century. Budge’s Coptic Psalter is kept in the British Library in London – the Mudil Codex is, however, kept in the Coptic Museum (MS. 6614), in Old Cairo, or what is called Coptic Cairo, in Egypt.

Figure 2: Map showing the location of Oxyrhynchos and Al-Madil (from Emmenegger’s book).

Figure 2: Map showing the location of Oxyrhynchos and Al-Madil (from Emmenegger’s book).

This priceless manuscript, as described by the Coptic Coptologist, Gawdat Gabra, is “The only biblical text discovered in an Egyptian tomb, it was found in the large, poor [Coptic] cemetery of Al-Mudil,[1] 40 kilometres north-east of Oxyrhynchos,[2] a city famous on Graeco-Roman times, in a shallow grave under a [Coptic] young girl’s head. Her parents must have been relatively rich to have owned such a valuable volume. The practice of burying religious texts with the dead dates back to Ancient Egyptian burial customs… the small peg used to lock the book is shaped like the ancient Egyptian symbol of life.”[3]

Unfortunately, no study of this gem has been done in English. Recently, in 2007, the German Coptologist Gregor Emmenegger wrote Der Text des koptischen Psalters aus al-Mudil. Ein Beitrag zur Textgeschichte der Septuaginta und zur Textkritik koptischer Bibelhandschriften, mit der kritischen Neuausgabe des Papyrus 37 der British Library London (U) und des Papyrus 39 der Leipziger Universitätsbibliothek (2013), which an extensive study of it. The publisher[4] writes:

The Mudil Codex from the late 4th century contains the Biblical Psalms in Coptic. However, the text differs significantly from familiar versions of the Psalms, giving rise to the question of whether we are dealing with an original form of the text. The comprehensive analysis presented here demonstrates the tradition in which this fascinating text is located, how it arose, and what significance it has for research into the Psalms generally and the Coptic Bible manuscripts in particular.

An good English review of the German book by Thomas J. Kraus in the Bryn Mawr Classical Review (2008.01.37), can be found here.

[1] Al-Madil is a small town in the eastern side of the Nile between Beni Suef and al-Bahnasa, Egypt.

[2] Oxyrhynchos, or Oxyrhynchus, is the Greek name (Coptic, Pemdje; modern town, el-Bahnasa or al-Bahnasa). It is a city in Upper Egypt in the governorate of Minya – some 100 miles southwest of Cairo. It is a rich archaeological site of Greek and Coptic papyri.

[3] Cairo: The Coptic Museum & Old Churches by Gawdat Gabra with contributions by Anthony Alcock (Cairo, Egyptian International Publishing Company – Longman, 1993); pp. 110-111.

[4] Walter de Gruyter, Berlin.

Figure 1: Rev. Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury (2002-2012).

Figure 1: Rev. Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury (2002-2012).

Many of you would know Rowan Williams (b. 1950) as the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury (2002 – 2012) and a man of intellect whose history at Cambridge and Oxford Universities is recognised, and an intellectual and theologian with wide interests.[1] When the American writer with much interest in Coptic monasticism, and author of so many books on the subject, Rev. Tim Vivian,[2] published The Coptic life of Antony by Saint Athanasius, which he translated,[3] he asked Rev. Williams to write a forward for the book. I like what Rowan Williams wrote, and this is what I would like to share with my readers here.

Now, Saint Antony[4] the Great (d. 356), the Egyptian ascetic, was not an ordinary man – he was intelligent without being lettered; he was a man of clear mind and strong faith; and he was a man of the sweetest of characters. His influence on Egypt’s Christianity, and in asceticism in general all over the world, cannot be overestimated. Saint Athanasius (d. 373), the 20th Coptic Patriarch of Alexandria, who wrote Vita S. Antoni (the Life of Saint Antony), too was a man of greatest intellect and faith, and his influence on Christianity is acknowledged by all. This combination of the two great minds, characters and saints – the subject of the autobiography and its author – in one book is what makes Vita S. Antoni one of the most beautiful books ever. And now, another intellect, Rev. Rowan Williams, adds to its brilliance by focusing on Chapters 72-80 of The Coptic Life of Antony, labelled “Antony and the [Pagan, Greek/Egyptian] Philosophers”[5]. He writes in his Forward to the book about the beauty of [Coptic] Christian asceticism, and the power and ascendancy of faith over Greek argumentative philosophy in bringing about real change in the lives of men:

In introducing this splendidly readable translation of the Coptic version of the first monastic classic, Tim Vivian speaks of it as a “frontier work”—a narrative that positions itself on the cutting edge of a new movement, pushing back existing boundaries. The boundaries in question are the habits and definition of Egyptian paganism: from the conclusion of the work,[6] we might gather that the translator has in view the average, not too bright rural believer, not the sophisticated Hellenic intellectual. The story is being told to show how Christian faith and monastic faithfulness quite simply expose an unreflective religious practice as slavery and deceit, unworthy of the dignity of human beings. And while we may be tempted to feel either superior or uncomfortable in the presence of this robust assertiveness, we need to hear what is being said. In Antony’s debates with the pagan philosophers, what is at issue is the importance of wisdom acquired in and expressed in action and commitment; even the pagans grant this in theory in the debate. Against what Christianity can offer, pagans practice can only bring forward nit-picking theorizing and empty religiosity—so the Christian narrator insists. The Christian ascetic, on the other hand, exhibits a life, an identy, that is attuned to reality, material and spiritual, and so has the only sort of power that matters, the power that comes from swimming strongly with the stream of truth. This is the power that sustains the monk in dereliction and temptation, that transfigures his physical presence and that exposes and overcomes the demonic slavery that prevails outside the Church, by miracles and exorcism.[7]

I thought it is remarkable that a 21st century Anglican Church leader, Rev. Rowan Williams, agrees with St. Antony, the 4th century Copt, that Christian faith beats philosophy in bringing about real change in the lives of ordinary men and women.

[1] He is now The Right Reverend and The Lord Williams of Oystermouth.

[2] Some of his works are: Counsels On The Spiritual Life: Mark The Monk; Becoming Fire: Through the Year with the Desert Fathers and Mothers; Saint Macarius, The Spirit Bearer: Coptic Texts Relating To Saint Macarius The Great; Four Desert Fathers: Pambo, Evagrius, Macarius of Egypt, and Macarius of Alexandria: Coptic Texts Relating to the Lausiac History of Pallad; St. Peter of Alexandria: Bishop and Martyr; Witness to Holiness: Abba Daniel of Scetis; Journeying into God, Seven Early Monastic Lives; Words to Live by: Journeys in Ancient and Modern Egyptian Monasticism; Histories of the Monks of Upper Egypt and the Life of Onnophrius. N.B. Some of these works are shared with others.

[3] The Coptic Life of Antony; translated by Tim Vivian (San Francisco – London, International Scholars Publications, 1995).

[4] Or Anthony.

[5] The Coptic Life of Antony; pp. 103-112. I cannot put a link to these chapters in Vivian’s translation; but the reader can read the relevant chapters in Life of Antony in Vo. IV of A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Athanasius: Select Works and Letters, here (Ch. 72-79) and here (Ch. 80). It is closely similar to what one finds in The Coptic Life of Antony.

[6] Rowan Williams refers to the last Chapter (94) of The Coptic Life of Antony, which is labelled “Concluding Exhortations and Doxology”. In the version in of A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church the chapter is simply labelled “The End”; and the reader can access it here.

[7] The Coptic Life of Antony; Forward; pp. i-ii.

Figure 1: A wedding group photo, at All saints Church, showing Mr And Mrs Butcher third and forth to the right of the bride in the centre. The photo is believed to include other prominent Anglican figures of the time, such as Re. Thornton and Dr Watson.[1]

Edith Louisa Butcher (or Mrs. E. L. Butcher) is a Coptic household name. Who doesn’t appreciate her writing “The Story of the Church of Egypt”, which has rendered a great service to the Coptic Church and nation? Nevertheless, there exists no biography of her. We practically know little of her life. I hope by writing this article I will help in building up an adequate Life of her, as others, hopefully, will add to it.[2]

She was born Edith Louisa Floyer on 13 February 1854 in Marshchapel, Grimsby, Lincolnshire, England. On 26 June 1896, at 42 years of age, she married Rev. Charles henry Butcher of Cairo, at St. Paul’s, Rome, Roma, Latium, Italy. After marriage, she moved with him to Cairo. Rev. Butcher, who was born in Clifton in 1833 and died in 1907 in Cairo, was Chaplain of the Anglican, All Saints Church (built 1878) in Azbakiyya, Cairo,[3] from 1880 to 1907, when he died at 74 years old age, was a major figure in the British community in Egypt after the British occupation in 1881; and he had a great influence in her. She called him “The Dean”, and says of his help, for example, “My History of the Egyptian Church was finished just about the time of my marriage to the Dean, else, as I afterwards told him, it would certainly never have been finished at all.”[4] Mrs Butcher survived her husband, and she died on 4 may 1933 in Devon, England, where she has been buried. I don’t know of any children of her.

Figure 2: Rev. Charles Henry Butcher, or The Dean, as Mrs Butcher calls him.[5]

Figure 2: Rev. Charles Henry Butcher, or The Dean, as Mrs Butcher calls him.[5]

Mrs E. L. Butcher showed a great interest and admiration in the Copts and their Church, and she wrote three important books that no one interested in Coptic matters should miss (click to access them):